How is Whiskey Made?

Last updated on November 12th, 2024

Sitting in your chair and swirling your glass, at some point you must have wondered “How on earth do they make this stuff?”

Well, in this article, I’ll walk you through each step of the process, from selecting the grains to the final bottling.

The Ingredients

Before we dive into the nitty-gritty of whiskey making, let’s talk about what actually goes into this beloved spirit. Believe it or not, the list is surprisingly short.

At its core, whiskey is made from just three main ingredients: grain, water, and yeast. That’s it. But don’t let the simplicity fool you – the magic is in how these ingredients are handled.

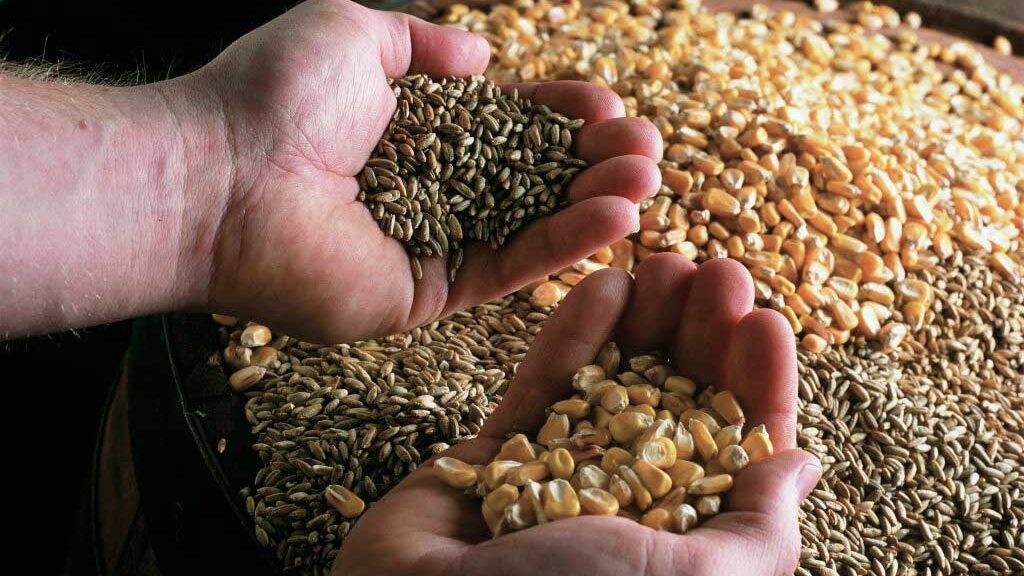

Grain is the star of the show, also known as cereal grains or ‘cereals’. The type of grain used can vary, and this is one of the key factors that distinguishes different styles of whiskey. Here’s a quick rundown:

- Barley: The go-to grain for Scotch, Irish and Japanese whiskey.

- Corn: The main player in bourbon, giving it that characteristic sweetness.

- Rye: Used heavily in Canadian whisky and American rye whiskey, adding a spicy kick.

- Wheat: Sometimes used to soften the flavor profile, especially in blends.

Water plays a crucial role too. It’s used throughout the process, from soaking the grains to diluting the spirit before bottling. Many distilleries pride themselves on their water sources, claiming it adds a unique character to their whiskey.

Last but not least, we have yeast. These microscopic fungi are the unsung heroes of whiskey making. They’re responsible for fermentation, naturally converting sugars into alcohol and producing many of the flavor compounds that make whiskey so complex.

Some distilleries use additional ingredients such as coloring to establish better consistency between batches. But for the most part, whiskey is a testament to how three simple ingredients, when treated with care and expertise, can create something truly extraordinary.

The Whiskey-Making Process

1. Malting

Malting is where the grain is tricked into germination by making it start to sprout and grow. Here’s how it works:

First, the grain (usually barley for malting) is soaked in water, multiple times. This kickstarts the germination process and small rootlets start to sprout, producing natural enzymes. These enzymes are crucial because they’ll later help convert the grain’s starches into sugars. It’s like the grain is doing some of the work for us.

Once the grain has sprouted just enough (we don’t want full-on plants), the germination is halted by drying the grain with hot air. This is typically done in a kiln. Here’s where things can get interesting. In Scotland, some distilleries use peat fires to dry their malted barley. This is what gives certain Scotch whiskies that distinctive smoky flavour. It’s like a little campfire in your glass.

2. Mashing

After malting, the malted grain is ground into a coarse flour called grist. Think of it like very rough whole wheat flour. This step increases the surface area of the grain, making it easier to extract all the fermentable sugars later in the process.

Next, the grist is mixed with hot water in a big vessel called a mash tun. It’s like making a giant, grainy porridge. The hot water activates those enzymes we created during malting, and they get to work breaking down the starches in the grain into sugars. Mashing is typically done in multiple stages, adding water at different temperatures and draining several times over. Each temperature draws out different sugars, giving us a more complex flavor profile in the end.

As this process continues, we end up with a sweet liquid called wort. It’s basically sugar water with a lot of flavor from the grains. If you’ve ever had the chance to taste wort, it’s surprisingly delicious – kind of like a very sweet, grainy tea. The solid parts of the grain, now stripped of their sugars, are separated from the liquid. These leftover grains, called draff, aren’t wasted – they’re often used as animal feed.

3. Fermentation

Now it’s time to turn the sweet, flavorful wort into alcohol. Enter fermentation, the step where some microscopic friends join the party.

The wort is transferred to large tanks called washbacks. These can be made of wood, stainless steel, or even concrete, depending on the distillery. Then yeast is added where it immediately (and frantically) feasts on the sugars in the wort, starting to produce alcohol and carbon dioxide as byproducts. At this stage, you essentially have a sort of grain beer.

But it’s not just alcohol the yeast is creating. During fermentation, a whole host of flavor compounds called congeners are produced. These contribute significantly to the final flavor of the whiskey.

The fermentation process usually takes around 48 to 96 hours, depending on the distillery. Some ferment for even longer, believing it creates more complex flavors. The liquid at the end of the fermentation process is called wash, and it usually has an alcohol content of about 7-10%.

Temperature plays a crucial role in fermentation. Too hot, and the yeast might produce off-flavors or die-off too quickly. Too cold, and the process might take too long. Distillers monitor temperature carefully to get the best results.

The type of yeast used can also impact the final flavor. Some distilleries use commercial yeast strains, while others have their own proprietary strains they’ve cultivated over years. A great example of this is the Four Roses distillery who have 5 different yeast strains to make their 10 bourbon recipes.

4. Distillation

Distillation is where the alcohol and flavors from fermentation are extracted from the beer using a simple principle: alcohol boils at a lower temperature than water, allowing them to be separated.

Most whiskeys are distilled twice in large copper stills. In Scotland and Ireland this is carried-out in traditional pot stills for single malts. Copper helps remove unwanted sulfur compounds, leading to a cleaner taste.

The first distillation happens in a large ‘wash still’ which produces an alcoholic liquid known as the ‘low wines’ at about 20-30% alcohol content.

The second distillation happens in a slightly smaller spirit still. This is where the low wines are re-distilled, producing much stronger alcoholic vapors which rise out the still-neck and recondense into ‘the run’ comprising of three stages;

- The heads: Harsh alcohols (discarded).

- The hearts: The good stuff kept for whiskey.

- The tails: Heavier compounds (kept aside).

Deciding when to make these “cuts” is crucial and greatly impacts the whiskey’s character. This is determined by the master distiller who observes the whiskey flowing through a transparent glass box known as ‘spirit safe’.

The final spirit is clear and high in alcohol (60-70% ABV) known as ‘white dog’ (in America) or ‘new make spirit’ (in Scotland). It’s got plenty of flavor, but it’s not quite whiskey yet. For that, it needs to be matured.

5. Maturation

Maturation is where the clear spirit becomes the complex whiskey we enjoy. The high-proof spirit is poured into wooden vessels, usually oak. In America, barrels are typically charred via fire and brand new (never having contained any alcohol before). In Scotland and Ireland, casks are typically made from ex-bourbon barrel staves imported from America.

In the barrel/cask, the whiskey:

- Gains color

- Reduces harsh flavors

- Gains new flavors from the wood

The environment matters too. Temperature changes cause the casks to “breathe,” speeding up wood-spirit interaction. A small portion is lost to evaporation known as the “angel’s share” and some is absorbed into the wood known as the “devil’s cut”.

Maturation time varies. Scotch must age at least 3 years, while straight bourbon needs 2. But longer isn’t always better – it’s about finding the perfect balance for the grains and casks used.

The skill is in knowing when a whiskey has reached its peak. It’s what makes master blenders so valuable in the industry.

When matured to perfection, the whiskey is ready for the final steps before bottling.

Variations in Process

Just when you think you’ve got whiskey-making figured out, think again! The beauty of this spirit lies in its diversity. Distilleries worldwide put their own spin on things, creating unique flavor profiles.

Scots often use peat-smoked barley (especially on the isle of Islay) giving Scotch its smoky character. Irish and Japanese distilleries do this too, but the use of peat is less common.

On the other hand, American whiskey is broadly made using various grain ratios which can include 2, 3 or even 4 cereals in one mash bill. For example, bourbon must use at least 51% corn, while rye whiskey uses 51% rye with the inclusion of wheat and a small portion of malted barley.

Even still shapes matter – tall, narrow ones produce lighter spirits, while shorter, fatter stills create more complex whiskeys. The variation in still design in Scotland and Ireland is vast, mainly due to use of traditional pot stills. Glenmorangie for example has the tallest pot stills in Scotland, standing at a staggering 5.13m (16 feet 10 inches).

Finishing is another variation of whiskey making which vastly impacts the final flavor. In Scotland and Ireland, different cask materials from different alcohols are widely used to tailor the taste. Sherry, wine, port, beer and even tequila casks can be used. Japanese distillers sometimes age in mizunara oak, adding distinct sandalwood notes.

Bottling and Finishing Touches

After years of patient waiting, the whiskey’s finally ready for its grand debut. But hold on, we’re not quite finished yet!

First, the whiskey is ‘cut’ with purified water to reduce it down to the desired alcohol content – typically around 40-46% ABV. Of course, certain whiskeys are bottled at cask strength with little to no dilution at all. These can be as strong as 60% ABV (120 proof).

Next comes filtration. Many distilleries use chill filtration to remove residues that might cloud the whiskey when it’s cold. However, some whiskey purists argue this strips away flavor, so you’ll often see “non-chill filtered” proudly declared on some bottles.

Finally, it’s bottling time. Whether it’s a blend or a single malt, each bottle is filled, corked, labeled, and boxed up, ready to bring joy to whiskey lovers worldwide.

FAQs

1. How long does whiskey need to age?

This depends on the type and where it’s made. Scotch and Irish whiskey must age at least 3 years. Bourbon has no minimum, but “straight” bourbon needs 2 years. Some whiskies age for decades! Remember, though: older doesn’t always mean better. It’s all about balance and flavor.

2. What’s the difference between whiskey and whisky?

Just spelling! “Whiskey” is used in Ireland and the US, while “whisky” is preferred in Scotland, Canada, and Japan. The spirit’s the same, so don’t fret over the extra “e”.

3. Does whiskey go bad after opening?

Not really. Unlike wine, whiskey doesn’t continue to age in the bottle. Once opened, it might slowly lose some aroma and flavor over several years, but it won’t “go bad”. Keep it sealed and away from direct sunlight, and it’ll be fine for a good long while.

4. What gives whiskey its color?

Whiskey gets most of its color from the barrel. ‘New make’ whiskey is crystal clear, but it soaks up color and flavor from the charred wooden staves of the barrel during aging. In Scotland and Ireland, caramel coloring is allowed to be added for production consistency.

5. Is making whiskey at home legal?

Home distillation is illegal in almost every country except for New Zealand. However, it’s perfectly legal to ferment your own beer, wine or cider for personal consumption.

Hopefully you found this article helpful.

Thanks for stopping by.